In conversation the topic of Blog-keeping comes up - is it just navel-gazing, an ego-trip, a textual 'folly' ... well, you can continue the objections.

I'm aware of an 'instrumentalist' logic at work which affects our daily lives in all sorts of ways. Notice the increasing number of programmes on the BBC based upon the idea of ransacking the attic for something to sell. The message seems to be: turn everything to a fast profit.

And so?

I like this statement by John Wilkinson in 'Quid' (I think you can access it online via barque press - I'm going by the magazine itself):

"... it remains important to assert that the journey matters more than arrival, for the arrival is at best disappointing and at its most predictable, deadly. To feel alive means to say, I went looking for this or that which I thought I wanted, and instead I found something which mattered to me far more."

He's talking about writing, of course, but it's a pretty good counterblast to people who insist on thinking everything has to have a definite outcome.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

"Like kindergarten 10 o'clock in the morning light"

Working by analogy from Philip Guston's paintings of the 1950s, is it possible to talk about light in the poem?

I remember Berrigan discussing light & colour in 'Talking in Tranquility', the interview with Tom Clark. He's explaining the effect of different times of day upon his - & other's - poems:

"Yeah. I also like to use the famous light at 5.15 a.m.. Like when the sun is sort of up, but it's only a quarter of the way up." (p.22)

However, is he implying more than simply notation? Putting it another way: can a poem have its own light?

Developing the analogy with Guston further*, how do we discern the equivalent of painterly 'touch' in a poem? Certain preferences for placement of verbs or adjectives? Tenses? Syntactical inversions or slippages? When/when not to break a line? A tendency to use long vowel sounds? Soft consonants? ... I'm going to think about this.

(* or, for that matter, Morton Feldman composing as described by Toru Takemitsu: "He was extremely nearsighted and wrote his music as if touching the notes with his eyes. Whenever I hear his music I think of its tactile quality, of his eyes ’hearing’ the sounds.")

I remember Berrigan discussing light & colour in 'Talking in Tranquility', the interview with Tom Clark. He's explaining the effect of different times of day upon his - & other's - poems:

"Yeah. I also like to use the famous light at 5.15 a.m.. Like when the sun is sort of up, but it's only a quarter of the way up." (p.22)

However, is he implying more than simply notation? Putting it another way: can a poem have its own light?

Developing the analogy with Guston further*, how do we discern the equivalent of painterly 'touch' in a poem? Certain preferences for placement of verbs or adjectives? Tenses? Syntactical inversions or slippages? When/when not to break a line? A tendency to use long vowel sounds? Soft consonants? ... I'm going to think about this.

(* or, for that matter, Morton Feldman composing as described by Toru Takemitsu: "He was extremely nearsighted and wrote his music as if touching the notes with his eyes. Whenever I hear his music I think of its tactile quality, of his eyes ’hearing’ the sounds.")

Monday, May 29, 2006

P.S.

oh & by the way, it's our anniversary today.

Mme Waffle does not read this Blog - at least so far as she's letting on. (D'you know there's a rainbow out the Velux window as I turn to find the right phrase - one that avoids sentimentality & yet hits sincerity smack in the face). I give up. It's gone now.

Anyway, just in case, here's to us & our collaborative poems - the two Brussels sprouts. Cheers!

Mme Waffle does not read this Blog - at least so far as she's letting on. (D'you know there's a rainbow out the Velux window as I turn to find the right phrase - one that avoids sentimentality & yet hits sincerity smack in the face). I give up. It's gone now.

Anyway, just in case, here's to us & our collaborative poems - the two Brussels sprouts. Cheers!

"Take a look at everyone"

Back to work & at eleven o'clock I find two packages from Amazon waiting in my pigeonhole. One contains Feldman's 'Rothko' CD, the other 'The Green Lake is Awake' by Joseph Ceravolo.

I shudder to think how many books I've ordered since January. That's enough for now - & this time I really mean it. Honest.

Sunday, May 28, 2006

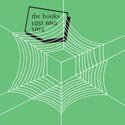

The sun is out & cooking with The Books

Yes, believe it or not. It may even be May.

Anyone following a few of the threads of this Blog will know why I am excited by this CD. Yesterday, it was the next CD behind the Boards of Canada discs I was looking through at the local mediatheque. Another example of while looking for something else, you find what you're really looking for.

I've only had a chance to listen to track one "a little longing goes away" but I already scent something interesting is going on. The printing of the CD booklet - a little volume in itself - ; those terrific webs; the predilection for lower case; the titles - "smells like content", "An Animated Description of Mr. Maps" - ; the (I assume) collage-derived lyrics ... As for the music, the collaging of voice in track one takes my discussion of Berrigan's Sonnets into a further dimension of recorded sound.

Their website is worth a look - http://www.thebooksmusic.com/ - & I wouldn't turn my nose up at the T-shirts or the oven gloves (yes - oven gloves). A sly tribute to Frank Zappa (see the back of 'Them or Us')? Or they just like food? Probably.

And if this wasn't enough, here's The Books in an interview:

"Voice is the most sonically heavy sound that people can make use of. It is so complex as a sound in itself, and at the same time it is capable of carrying literary meaning and personal identity. Human ears evolved around using it and understanding it, so it is a powerful tool in music. Everything is so strange and wonderful when you listen carefully, it is hard to believe that ‘commonplace’ really exists."

Belgianwaffle's CD of the week. My ears are hungry for more.

Saturday, May 27, 2006

How many hours in the day?

I see Jonathan Mayhew - aka Bemsha Swing - is asking for questions for his students concerning their approach to a text. I'd approach it from a slightly different angle: what to read, when to read it, how to read it?

For example, I am currently reading Emily Dickinson - I've arrived at poem 300 or thereabouts. Only another 1,400 to go! Simultaneously, I am reading Feldman's essays, the new Guston book, poems by Graham Foust & Devin Johnston... This is before taking into consideration magazines such as The Wire, the LRB, Chicago Review. Then there's the Blogs ... And what about contextual reading - the Whitehead, for instance? And whatever you just pick up by chance - Rebecca Solnit's new volume... The list goes on. And that's just the reading - the films, the exhibitions?

Mondays to Fridays there's the day job. Weekends there's things to do 'en famille'. Each day I am committed to a daily walk. And now I'm keeping up a Blog.

The 'window' for reading shrinks. There, that's something for students to think about - I know I didn't.

For example, I am currently reading Emily Dickinson - I've arrived at poem 300 or thereabouts. Only another 1,400 to go! Simultaneously, I am reading Feldman's essays, the new Guston book, poems by Graham Foust & Devin Johnston... This is before taking into consideration magazines such as The Wire, the LRB, Chicago Review. Then there's the Blogs ... And what about contextual reading - the Whitehead, for instance? And whatever you just pick up by chance - Rebecca Solnit's new volume... The list goes on. And that's just the reading - the films, the exhibitions?

Mondays to Fridays there's the day job. Weekends there's things to do 'en famille'. Each day I am committed to a daily walk. And now I'm keeping up a Blog.

The 'window' for reading shrinks. There, that's something for students to think about - I know I didn't.

Friday, May 26, 2006

For a rainy day

Find a book on Philip Guston down to 19 euros (from 45 euros).

On page 36:

"The famous exchange that took place at Guston's studio when Feldman brought Cage to see Guston's recent paintings in the early 1950s summarizes their philosophical dialectics at the time. Cage's remark, "My God, it's possible to paint a magnificent picture about nothing" was rejoined by Feldman's, "But, John, it's about everything."

(Yesterday's post on 'Hejira' needs much more consideration of the performative aspect of her voice. How lines are actually delivered. And, inevitably, the music itself.)

On page 36:

"The famous exchange that took place at Guston's studio when Feldman brought Cage to see Guston's recent paintings in the early 1950s summarizes their philosophical dialectics at the time. Cage's remark, "My God, it's possible to paint a magnificent picture about nothing" was rejoined by Feldman's, "But, John, it's about everything."

(Yesterday's post on 'Hejira' needs much more consideration of the performative aspect of her voice. How lines are actually delivered. And, inevitably, the music itself.)

Thursday, May 25, 2006

blowing on subject of image

I’m not a great ‘Joni fan’ but one song – ‘Hejira’ – exerts a mesmerizing power. I don’t know if this is due to simple association, one of those songs which you cannot hear without remembering rooms and occasions, making the lyric content effectively irrelevant. Maybe. Or perhaps it is the musical composition and performance, Pastorius’ bass being especially evocative. Or do Mitchell’s lyrics possess a power of their own? Should song lyrics be able to sustain the same level of scrutiny as a poem intended for the page?

Let’s see.

First, I’m struck by how the centred lyrics in the CD booklet lose the run-on effect of the writing. I wouldn’t go so far as to break the lines into 4-line verses either – although it’s clear she’s working an abcb rhyme throughout. I notice, too, that she tends to employ quite open vowel rhymes – “café”/”away”, “resign”/”line” – allowing for the singing voice to linger and reinforce the wistful mood of the song’s argument.

Next, the unabashed use of “I” in full autobiographical mode. There seems no possibility of taking this as a ‘persona’. Even when Mitchell claims “I see something of myself in everyone” this seems very different to Whitman’s “I” containing “multitudes”. This is not a transcendence of Self but its intensification. If you like Mitchell’s albums then you buy into this confessional “I”. If not, you better look elsewhere.

I detect Beat influences – or, at least, sympathies - in her spooling lines, the ‘on the road’ scenario as the fundamental metaphor of male-female relationships. The generic “vehicle” and “café” in which she finds herself are also suggestive of hip, bohemian lifestyles. Furthermore, the upfrontness of feeling, MY pain, MY suffering has a sexual politics that has to be considered against simple narcissism.

Looking at the lyric as 4-line verses, a recurrent tendency emerges in terms of Mitchell’s handling of imagery. She has a liking for a two-line assertion – typically of feelings or a philosophical truism which is then ‘grounded’ by an image. For example:

“There’s a comfort in melancholy

When there’s no need to explain

It’s just as natural as the weather

In this moody sky today”

There are two interesting qualifications – i) where the image (typically from nature) is itself anthropomorphicized – “moody weather”; ii) where the image itself is highly abstract – “Whether you travel the breadth of extremities/Or stick to some straighter line”. The latter image would not be out of place in an Emily Dickinson poem.

However, it is in these lines that the song seems to crystallize:

"White flags of winter chimneys

Waving truce against the moon

In the mirrors of a modern bank

From the window of a hotel room”

In terms of argument, the climax would seem to be lines 29-32 (“I know – no one’s going to show me everything/We all come and go unknown/Each so deep and superficial/Between the forceps and the stone”) but – to my mind – she is being too explicit, too much is being asserted, the imagery too available.

What’s so powerful about the “White flags” sequence is the absence of explicit statement – although the idea of surrender can easily be related back to the “petty wars” of the opening lines. There is something compelling about the movement from overtly ‘poetic’ images (snow plus moon) to the ‘realism’ of finance and modern architecture, coupled with two shifts of perspective (the chimneys reflected in windows, themselves seen from a room, by implication the viewer/singer detached and lost). Imagine Zukofsky being given the lyric – might these be the lines he’d leave intact?

Yet what might satisfy the Objectivist might not work so well as a song lyric. For the power of these lines is inseparable from the gradual build-up of sounds & cadence. Mitchell’s lyrics have their own music – before we need to talk about the instrumentation. Taking lines 29-32 again, listen to the ‘o’ sound as it echoes through “know”, “no one”, “going”, “show”, “go”, “so”, “stone” – arguing against my earlier accusation about the “forceps:stone” imagery. Sound-wise it is merited. Now turn up the music itself and lyric and composition work to reinforce each other as the bass – always that bass – sounds those mournful “o’s”.

I’m not sure what to do with Mitchell’s – probably? – unconscious punning (“Benny/bene”, “Goodman/good man”, “porous/poor us”) but who cares? Her voice ‘plays’ the words adding meanings by means of intonation. Her vocal is – as such – the top part. This is the melody, the sax solo. Her lines achieve - like Kerouac at his best - that breathing “beat”. Maybe that’s what works the magic?

Let’s see.

First, I’m struck by how the centred lyrics in the CD booklet lose the run-on effect of the writing. I wouldn’t go so far as to break the lines into 4-line verses either – although it’s clear she’s working an abcb rhyme throughout. I notice, too, that she tends to employ quite open vowel rhymes – “café”/”away”, “resign”/”line” – allowing for the singing voice to linger and reinforce the wistful mood of the song’s argument.

Next, the unabashed use of “I” in full autobiographical mode. There seems no possibility of taking this as a ‘persona’. Even when Mitchell claims “I see something of myself in everyone” this seems very different to Whitman’s “I” containing “multitudes”. This is not a transcendence of Self but its intensification. If you like Mitchell’s albums then you buy into this confessional “I”. If not, you better look elsewhere.

I detect Beat influences – or, at least, sympathies - in her spooling lines, the ‘on the road’ scenario as the fundamental metaphor of male-female relationships. The generic “vehicle” and “café” in which she finds herself are also suggestive of hip, bohemian lifestyles. Furthermore, the upfrontness of feeling, MY pain, MY suffering has a sexual politics that has to be considered against simple narcissism.

Looking at the lyric as 4-line verses, a recurrent tendency emerges in terms of Mitchell’s handling of imagery. She has a liking for a two-line assertion – typically of feelings or a philosophical truism which is then ‘grounded’ by an image. For example:

“There’s a comfort in melancholy

When there’s no need to explain

It’s just as natural as the weather

In this moody sky today”

There are two interesting qualifications – i) where the image (typically from nature) is itself anthropomorphicized – “moody weather”; ii) where the image itself is highly abstract – “Whether you travel the breadth of extremities/Or stick to some straighter line”. The latter image would not be out of place in an Emily Dickinson poem.

However, it is in these lines that the song seems to crystallize:

"White flags of winter chimneys

Waving truce against the moon

In the mirrors of a modern bank

From the window of a hotel room”

In terms of argument, the climax would seem to be lines 29-32 (“I know – no one’s going to show me everything/We all come and go unknown/Each so deep and superficial/Between the forceps and the stone”) but – to my mind – she is being too explicit, too much is being asserted, the imagery too available.

What’s so powerful about the “White flags” sequence is the absence of explicit statement – although the idea of surrender can easily be related back to the “petty wars” of the opening lines. There is something compelling about the movement from overtly ‘poetic’ images (snow plus moon) to the ‘realism’ of finance and modern architecture, coupled with two shifts of perspective (the chimneys reflected in windows, themselves seen from a room, by implication the viewer/singer detached and lost). Imagine Zukofsky being given the lyric – might these be the lines he’d leave intact?

Yet what might satisfy the Objectivist might not work so well as a song lyric. For the power of these lines is inseparable from the gradual build-up of sounds & cadence. Mitchell’s lyrics have their own music – before we need to talk about the instrumentation. Taking lines 29-32 again, listen to the ‘o’ sound as it echoes through “know”, “no one”, “going”, “show”, “go”, “so”, “stone” – arguing against my earlier accusation about the “forceps:stone” imagery. Sound-wise it is merited. Now turn up the music itself and lyric and composition work to reinforce each other as the bass – always that bass – sounds those mournful “o’s”.

I’m not sure what to do with Mitchell’s – probably? – unconscious punning (“Benny/bene”, “Goodman/good man”, “porous/poor us”) but who cares? Her voice ‘plays’ the words adding meanings by means of intonation. Her vocal is – as such – the top part. This is the melody, the sax solo. Her lines achieve - like Kerouac at his best - that breathing “beat”. Maybe that’s what works the magic?

Just at this moment of the world

i)

“This is the morning, after the dispersion, and the work of the morning is methodology: how to use oneself, and on what. That is my profession. I am an archaeologist of morning.”

(‘The Present is Prologue’, Charles Olson)

ii)

“All memorable events, I should say, transpire in morning time and in a morning atmosphere. The Vedas say, "All intelligences awake with the morning." Poetry and art, and the fairest and most memorable of the actions of men, date from such an hour. All poets and heroes, like Memnon, are the children of Aurora, and emit their music at sunrise. To him whose elastic and vigorous thought keeps pace with the sun, the day is a perpetual morning.”

(‘Where I lived, and what I lived for”, ‘Walden’, Thoreau)

iii)

“Be awake mornings. See light spread across the lawn”

(‘Crystal’, Ted Berrigan)

iv)

“How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?”

(Greek sophist Meno, cited by Rebecca Solnitt in ‘A Field Guide to Getting Lost’)

v)

“I know – no one’s going to show me everything”

(‘Hejira’, Joni Mitchell)

Walking, reading, listening.

“This is the morning, after the dispersion, and the work of the morning is methodology: how to use oneself, and on what. That is my profession. I am an archaeologist of morning.”

(‘The Present is Prologue’, Charles Olson)

ii)

“All memorable events, I should say, transpire in morning time and in a morning atmosphere. The Vedas say, "All intelligences awake with the morning." Poetry and art, and the fairest and most memorable of the actions of men, date from such an hour. All poets and heroes, like Memnon, are the children of Aurora, and emit their music at sunrise. To him whose elastic and vigorous thought keeps pace with the sun, the day is a perpetual morning.”

(‘Where I lived, and what I lived for”, ‘Walden’, Thoreau)

iii)

“Be awake mornings. See light spread across the lawn”

(‘Crystal’, Ted Berrigan)

iv)

“How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?”

(Greek sophist Meno, cited by Rebecca Solnitt in ‘A Field Guide to Getting Lost’)

v)

“I know – no one’s going to show me everything”

(‘Hejira’, Joni Mitchell)

Walking, reading, listening.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Summer is a-cummin in

The bikini ads have blossomed.

Everywhere you look in Brussels there's a billboard of a girl, her left arm crooked behind her head, her face in a state of either semi-arousal or intoxication from the enchanting aromas wafting from her armpit. What's certain is that in this rain-lashed city, she must be feeling decidedly chilly... .

Everywhere you look in Brussels there's a billboard of a girl, her left arm crooked behind her head, her face in a state of either semi-arousal or intoxication from the enchanting aromas wafting from her armpit. What's certain is that in this rain-lashed city, she must be feeling decidedly chilly... .

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

... which is as much to say ...

"Our engagement with knowing, with craft and lore, our demand for truth is not to reach a conclusion but to keep our exposure to what we do not know, to confront our wish and our need beyond habit and capability, beyond what we can take for granted, at the borderline, the light fingertip or thought tip where impulse and novelty spring." (Robert Duncan)

"... and I don't know the people who will feed me..."

In the car this morning listening to Mark E. Smith explaining how he’s "dislearned a lot of things”. I then open Ron Silliman's Blog and read his remarks on Charles Olson who claimed:

"I have had to learn the simplest things

last. Which made for difficulties."

They're both pretty good descriptions of the reading & thinking I have been doing -– and a useful theme for this Blog. An ongoing outgrowing of what Jack Spicer called "The English Department of the spirit - that great quagmire that lurks at the bottom of all of us”. I know exactly what he means.

So, I'm prepared to take the risk, put some ideas 'out for tender', go back to basics. There will be people who have read more, written more, cornered the territory, have greater theoretical rigour. However, the kinds of writing I admire most seem to demand a generosity of reading and discussion - an openness of mind, if you like. I'm not aiming at tenure - I'm trying to start a few conversations, air a few ideas.

Teaching Frank O'Hara's 'The Day Lady Died' yesterday, I was struck for the first time by a thematics of 'company'. The dinner engagement, the purchasing of gifts, the interdependence of each named writer. Hesiod is translated by Richmond Lattimore, Genet and Behan - as playwrights - require actors, Verlaine is illustrated by Bonnard. Even Billie Holiday has her piano accompanist Mal Waldron. It's as if O'Hara is suggesting everyone needs someone to enable them to sing.

It's sad, really, how strenuously we think ourselves into being alone.

"I have had to learn the simplest things

last. Which made for difficulties."

They're both pretty good descriptions of the reading & thinking I have been doing -– and a useful theme for this Blog. An ongoing outgrowing of what Jack Spicer called "The English Department of the spirit - that great quagmire that lurks at the bottom of all of us”. I know exactly what he means.

So, I'm prepared to take the risk, put some ideas 'out for tender', go back to basics. There will be people who have read more, written more, cornered the territory, have greater theoretical rigour. However, the kinds of writing I admire most seem to demand a generosity of reading and discussion - an openness of mind, if you like. I'm not aiming at tenure - I'm trying to start a few conversations, air a few ideas.

Teaching Frank O'Hara's 'The Day Lady Died' yesterday, I was struck for the first time by a thematics of 'company'. The dinner engagement, the purchasing of gifts, the interdependence of each named writer. Hesiod is translated by Richmond Lattimore, Genet and Behan - as playwrights - require actors, Verlaine is illustrated by Bonnard. Even Billie Holiday has her piano accompanist Mal Waldron. It's as if O'Hara is suggesting everyone needs someone to enable them to sing.

It's sad, really, how strenuously we think ourselves into being alone.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Feedback problems

One or two people have said they can't post comments. I'm not sure why - something about setting up a profile. If you do want to contribute, express disagreement, or just say you've dropped by then there's always my e-mail (belgianwaffle@hotmail.com).

We are the sleeping fragments of his sky

It was Miles Champion who first put me on to Ted Berrigan’s ‘Sonnets’ in his review of the Penguin ‘Selected Poems’ printed in ‘Parataxis’. It must have been about 1995. I liked the poems immediately – they seemed exciting in suggesting what a poem could be. An exhilirating break from the narrow confines of what I had to teach for the GCSE & A level syllabuses (Hughes, Larkin, Plath …). Ironically, it was very much a reaction at the level of content: disconcertingly honest references to drug taking, burger buying, little incidents of New York street life. I had already got this from O’Hara (by then I had got hold of his 'Selected Poems' from Carcanet & 'Lunch Poems') but Berrigan seemed to go even further, or was more ‘pally’, or – be honest – the poems seemed rather crudely made & anyone could do it. How wrong could I be?

Now, ten years on, I’m only beginning to see what is going on in ‘The Sonnets’ and quite how well made they are. I’ve noticed this with a lot of poetry - how by reading other poets, other books unrelated to poetry, walking around, letting things settle, so a group of poems start to speak differently. Go at the poems too directly and they freeze. Old habits of reading assert themselves.

I’m misrembering a quote in this month’s ‘Wire’ but it applies to poetry: each poet creates a new ear. You have to allow yourself to hear free of preconceptions.

In a way, Berrigan’s ‘Sonnets’ work a little like venetian blinds. I’m thinking of each poem being made up of slats which can be independently turned. Reading the poems in the mid 90s I was looking ‘through’ the slats, seeing the world ‘behind’ – and the poems can work in this way. ‘The Sonnets’ then read as a socio-poetic record of 60s bohemian living, Berrigan’s autobiography, his habits, his walks, his talks, his pills, so many cans of Pepsi.

However, reading the poems now, I see how the lines ‘angle’. How, rather than effacing themselves before a ‘Real’ going on behind, they flatten themselves. Berrigan confronts you with the line on the page. Look at it. Listen to it. Don’t immediately jump through it.

How persuasive is the first line of Sonnet II:

“Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m.”

Ignoring for a moment the latent absurdity/oddity (who phones that early in the morning?), the poignancy (Berrigan is addressing a lost love as he sits lonely at this early hour?), the humour (and Berrigan is funny), the line seems so factual. So direct. The mode of address. The proper name. The time on the clock. Everything conspires to create a sense of ‘the real’.

Now ‘turn’ the slat. First, Berrigan’s knowing borrowing/homage to O’Hara’s signature opening – the “I do this, I do that” style:

“It is 12:20 in New York a Friday” (‘The Day Lady Died’)

already the 5:15 a.m. ‘now’ of Berrigan’s poem is co-terminus with O’Hara’s 12:20. There’s clock time and there’s poetic time. The entire enterprise of ‘The Sonnets’ is also a knowing dialogue with the sonnet tradition – one of the yardsticks of poetic achievement and skill – Shakespeare’s sequence in particular. Berrigan, at 5:15 a.m. is speaking ‘back’ to a whatever time on the clock in 1590 or thereabouts.

Second, the sounds. I simply hadn’t heard Berrigan’s lines. Listen:

The long ‘e’ echoing between “dear” and “Margie” and the “teen” of “15”. The long “i”, long “o”, and long “a” of the abbreviated “a” (in a.m.) which will then be worked across other lines in the sonnet. The diaristic style, the abbreviations, the numbers all suggest a casualness. Yet how calculated they are. And this is central to Berrigan’s aesthetic: the language of the everyday and everyman yields its poetry.

Third, collage. Alice Notley in her introduction reinforces the idea that Berrigan ‘built’ these poems, words working like bricks. I think it is important to do away with the typically (Romantic?) stereotype of poetic composition – poet struck by a flash of inspiration madly scribbling his lines before the Muse vanishes – and replace it with an image of the poet sat at a typewriter surrounded with notebooks, open books, abandoned drafts, phrases pinned to the wall seeing what will ‘fit’. Not to say a line won’t come ‘just like that’. But the evidence suggests Berrigan worked with phrases as raw material. (Certain sonnets are completely ‘plundered’, Berrigan’s lectures are full of admissions about his stealing ‘good lines’, his little address books full of overheard remarks).

It would be stupid to see this as a sign of failure or lack of creativity – Berrigan ‘simply’ appropriating other people’s lines. Rather, look at what he does with them. How the method of construction becomes integral to the work.

As Cage realised, modern technology of sound recording liberated composers. You could now ‘compose’ with any sound not simply those noises produced by the orchestra. There is a similar opportunity for the modern poet. Who cares whether Berrigan really said “Hello Marge” , whether it was “5:15 a.m.” (in fact, it is only us assuming the two statements are linked). We don’t even need to know who Marge is (although the notes will identify the likely candidate). The point is that the line now works as compositional material.

There’s no denying that Berrigan will have his cake and eat it. He does want the ‘pull’ of referents – girlfriends, passing time, early morning atmospheres, the hip feel of being alive and a poet in New York. He does want the themes – yes, the Big Ones: Time. Love. Death. etc. He does want the formal integrity and pleasures offered by the poetic music. Yet … what do we get on line 12?

“Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m.”

Line one repeated. An immediate flattening. So simple and yet so effective. It’s not even a self-citation. Simply line one re-typed – making us acknowledge that it is all being typed. Collapse of the ‘real’ effect. Now, the realisation that language is being arranged according to logics independent of (although not excluding) ‘real life’, the anecdotal moment. Or, to put it better, ‘real life’, the lived moment enters the poem but not as its own justification. Berrigan’s poems are NOT simply ‘of the moment’. There are several logics of ‘now’ at work.

It is here I return to the earlier post on Morton Feldman. What Cage identified as “acceptance” as a compositional procedure in Feldman, I also see at work in Berrigan. It can’t be denied that Ezra Pound had employed collage techniques in ‘The Cantos’ (no coincidence that Pound figures in Sonnet I “His piercing pince-nez”) and had already broken with the ‘ancedotal’ model. Lines compose to create The Image’. What – as I see it – Berrigan does is to deliberately collapse the ‘space’by playing off modes of representation. “This is taking place right now – oh no it isn’t! these are just words on the page”). Furthermore, the material is no longer ‘sanctified’ by poetic aura. The most casual phrase, the most banal observation, is now available for composition. Life is let in to – becomes the grounds for – Art.

Furthermore, lived experience undergoes a transformation through composition as Berrigan plunders his own (earlier) poems – this he claimed was the sudden ‘breakthrough’ insight at the start of the project. (For a similar technique in music, see Zappa’s practice of ‘xenochrony’ involving collaging of live recording and studio sessions into original/recorded compositions).

And – as if this wasn’t enough – the seemingly constrictive & exhausted form of the sonnet is revitalized as it allows lines to be juxtaposed & thereby acquire unexpected meanings through placement. The tightness of the 14-line form works to Berrigan’s advantage. Anything longer and you’d lose the internal echos and reflections. Anything shorter and there’d not be enough to work on.

Each line is a strip which then acquires an ongoing ‘glue’ of sense through the line by line reading of the poem. Needless to say, this principle can then be extended beyond the individual poem to the ‘macro’ level of the sequence. Lines reoccur, trailing with them their previous contexts (by now an inextricable complex of ‘real’ + ‘literary’ + ‘textual’ meanings) to then undergo further recomposition/decomposition in their new placement. And it can only follow on from this that by Sonnet X, Sonnet I has already started to read rather differently. These poems develop in multiple directions.

Those audacious second and third lines:

“dear Berrigan. He died

Back to books. I read”

I’ll save for next time a discussion of Berrigan’s use of line and punctuation.

(Yes, I know. I really should read Alfred North Whitehead…)

Now, ten years on, I’m only beginning to see what is going on in ‘The Sonnets’ and quite how well made they are. I’ve noticed this with a lot of poetry - how by reading other poets, other books unrelated to poetry, walking around, letting things settle, so a group of poems start to speak differently. Go at the poems too directly and they freeze. Old habits of reading assert themselves.

I’m misrembering a quote in this month’s ‘Wire’ but it applies to poetry: each poet creates a new ear. You have to allow yourself to hear free of preconceptions.

In a way, Berrigan’s ‘Sonnets’ work a little like venetian blinds. I’m thinking of each poem being made up of slats which can be independently turned. Reading the poems in the mid 90s I was looking ‘through’ the slats, seeing the world ‘behind’ – and the poems can work in this way. ‘The Sonnets’ then read as a socio-poetic record of 60s bohemian living, Berrigan’s autobiography, his habits, his walks, his talks, his pills, so many cans of Pepsi.

However, reading the poems now, I see how the lines ‘angle’. How, rather than effacing themselves before a ‘Real’ going on behind, they flatten themselves. Berrigan confronts you with the line on the page. Look at it. Listen to it. Don’t immediately jump through it.

How persuasive is the first line of Sonnet II:

“Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m.”

Ignoring for a moment the latent absurdity/oddity (who phones that early in the morning?), the poignancy (Berrigan is addressing a lost love as he sits lonely at this early hour?), the humour (and Berrigan is funny), the line seems so factual. So direct. The mode of address. The proper name. The time on the clock. Everything conspires to create a sense of ‘the real’.

Now ‘turn’ the slat. First, Berrigan’s knowing borrowing/homage to O’Hara’s signature opening – the “I do this, I do that” style:

“It is 12:20 in New York a Friday” (‘The Day Lady Died’)

already the 5:15 a.m. ‘now’ of Berrigan’s poem is co-terminus with O’Hara’s 12:20. There’s clock time and there’s poetic time. The entire enterprise of ‘The Sonnets’ is also a knowing dialogue with the sonnet tradition – one of the yardsticks of poetic achievement and skill – Shakespeare’s sequence in particular. Berrigan, at 5:15 a.m. is speaking ‘back’ to a whatever time on the clock in 1590 or thereabouts.

Second, the sounds. I simply hadn’t heard Berrigan’s lines. Listen:

The long ‘e’ echoing between “dear” and “Margie” and the “teen” of “15”. The long “i”, long “o”, and long “a” of the abbreviated “a” (in a.m.) which will then be worked across other lines in the sonnet. The diaristic style, the abbreviations, the numbers all suggest a casualness. Yet how calculated they are. And this is central to Berrigan’s aesthetic: the language of the everyday and everyman yields its poetry.

Third, collage. Alice Notley in her introduction reinforces the idea that Berrigan ‘built’ these poems, words working like bricks. I think it is important to do away with the typically (Romantic?) stereotype of poetic composition – poet struck by a flash of inspiration madly scribbling his lines before the Muse vanishes – and replace it with an image of the poet sat at a typewriter surrounded with notebooks, open books, abandoned drafts, phrases pinned to the wall seeing what will ‘fit’. Not to say a line won’t come ‘just like that’. But the evidence suggests Berrigan worked with phrases as raw material. (Certain sonnets are completely ‘plundered’, Berrigan’s lectures are full of admissions about his stealing ‘good lines’, his little address books full of overheard remarks).

It would be stupid to see this as a sign of failure or lack of creativity – Berrigan ‘simply’ appropriating other people’s lines. Rather, look at what he does with them. How the method of construction becomes integral to the work.

As Cage realised, modern technology of sound recording liberated composers. You could now ‘compose’ with any sound not simply those noises produced by the orchestra. There is a similar opportunity for the modern poet. Who cares whether Berrigan really said “Hello Marge” , whether it was “5:15 a.m.” (in fact, it is only us assuming the two statements are linked). We don’t even need to know who Marge is (although the notes will identify the likely candidate). The point is that the line now works as compositional material.

There’s no denying that Berrigan will have his cake and eat it. He does want the ‘pull’ of referents – girlfriends, passing time, early morning atmospheres, the hip feel of being alive and a poet in New York. He does want the themes – yes, the Big Ones: Time. Love. Death. etc. He does want the formal integrity and pleasures offered by the poetic music. Yet … what do we get on line 12?

“Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m.”

Line one repeated. An immediate flattening. So simple and yet so effective. It’s not even a self-citation. Simply line one re-typed – making us acknowledge that it is all being typed. Collapse of the ‘real’ effect. Now, the realisation that language is being arranged according to logics independent of (although not excluding) ‘real life’, the anecdotal moment. Or, to put it better, ‘real life’, the lived moment enters the poem but not as its own justification. Berrigan’s poems are NOT simply ‘of the moment’. There are several logics of ‘now’ at work.

It is here I return to the earlier post on Morton Feldman. What Cage identified as “acceptance” as a compositional procedure in Feldman, I also see at work in Berrigan. It can’t be denied that Ezra Pound had employed collage techniques in ‘The Cantos’ (no coincidence that Pound figures in Sonnet I “His piercing pince-nez”) and had already broken with the ‘ancedotal’ model. Lines compose to create The Image’. What – as I see it – Berrigan does is to deliberately collapse the ‘space’by playing off modes of representation. “This is taking place right now – oh no it isn’t! these are just words on the page”). Furthermore, the material is no longer ‘sanctified’ by poetic aura. The most casual phrase, the most banal observation, is now available for composition. Life is let in to – becomes the grounds for – Art.

Furthermore, lived experience undergoes a transformation through composition as Berrigan plunders his own (earlier) poems – this he claimed was the sudden ‘breakthrough’ insight at the start of the project. (For a similar technique in music, see Zappa’s practice of ‘xenochrony’ involving collaging of live recording and studio sessions into original/recorded compositions).

And – as if this wasn’t enough – the seemingly constrictive & exhausted form of the sonnet is revitalized as it allows lines to be juxtaposed & thereby acquire unexpected meanings through placement. The tightness of the 14-line form works to Berrigan’s advantage. Anything longer and you’d lose the internal echos and reflections. Anything shorter and there’d not be enough to work on.

Each line is a strip which then acquires an ongoing ‘glue’ of sense through the line by line reading of the poem. Needless to say, this principle can then be extended beyond the individual poem to the ‘macro’ level of the sequence. Lines reoccur, trailing with them their previous contexts (by now an inextricable complex of ‘real’ + ‘literary’ + ‘textual’ meanings) to then undergo further recomposition/decomposition in their new placement. And it can only follow on from this that by Sonnet X, Sonnet I has already started to read rather differently. These poems develop in multiple directions.

Those audacious second and third lines:

“dear Berrigan. He died

Back to books. I read”

I’ll save for next time a discussion of Berrigan’s use of line and punctuation.

(Yes, I know. I really should read Alfred North Whitehead…)

Sunday, May 21, 2006

A poetics of space?

Everyone has their own architecture. A private phenomenology of spaces. And mine?

Cloisters. Avenues. The tree-lined paths through the Foret des Soignes (now there's a cathedral). The MAC gallery at Le Grand Hornu where every room has a connection with the exterior. Conservatories with full length windows preferably sliding open onto the garden. Canal-fronting houses in Amsterdam with their uncurtained windows. Stonehenge. Tintern Abbey. Attic bedrooms with Velux windows through which you can see the night sky. Bus shelters (so many fruitful hours spent standing ‘in’ these) …

My instinctive gesture: to open a window. The bathroom window (tooth brushing). Kitchen window (kettle on). Bedroom window (to hear the occasional car, rain, birds singing).

And spaces I hate? Hermetic spaces: Eurostar compartments, aircraft, ‘in camera’ meetings, assemblies, conference hotels with air conditioning and sealed windows, hospital waiting rooms, dinner parties when the food is eaten and the talk has been exhausted.

The definition of a ‘good’ space? One where outside and inside communicate. The air flows. The exits are clearly marked. There is space to breathe.

And, it has just occurred to me – a web.

Cloisters. Avenues. The tree-lined paths through the Foret des Soignes (now there's a cathedral). The MAC gallery at Le Grand Hornu where every room has a connection with the exterior. Conservatories with full length windows preferably sliding open onto the garden. Canal-fronting houses in Amsterdam with their uncurtained windows. Stonehenge. Tintern Abbey. Attic bedrooms with Velux windows through which you can see the night sky. Bus shelters (so many fruitful hours spent standing ‘in’ these) …

My instinctive gesture: to open a window. The bathroom window (tooth brushing). Kitchen window (kettle on). Bedroom window (to hear the occasional car, rain, birds singing).

And spaces I hate? Hermetic spaces: Eurostar compartments, aircraft, ‘in camera’ meetings, assemblies, conference hotels with air conditioning and sealed windows, hospital waiting rooms, dinner parties when the food is eaten and the talk has been exhausted.

The definition of a ‘good’ space? One where outside and inside communicate. The air flows. The exits are clearly marked. There is space to breathe.

And, it has just occurred to me – a web.

How do you focus your ear?

Morton Feldman. First thoughts. How often a volume, a piece of music, an exhibition comes at the right time. Sense of uncanny synchronicity. Or is it simply changes within your own living, breathing, thinking which allow a greater receptivity? Above all to be responsible (Robert Duncan) – ie able to respond.

Feldman’s music intrigues me. It comes at the right time given my current reading & preoccupations. (Although during the MOMA Guston exhibition in Oxford circa 1987-8 wouldn’t have been a bad time, would it?). Still, we orbit.

How do you focus your ear? That seems to be a major issue with Feldman’s music. Cage, of course, wished his readers ‘Happy New Ears’. And it is not once every 365 days but here, now, this very second.

Which leads to a consideration of time. Feldman cites Varese & the “time sound needs in order to speak”. What is sound? What is a note in fact?

Feldman’s music demands a re-thinking of the material nature of sound. The note is struck – a physical action involving musician plus instrument (eg. piano = hammer plus strings) – which sets the air molecules “wiggling” (Zappa). The note is – as such – an after-image, a shadow. Feldman’s compositions are thus “thin air”. An “airy nothingness” suggestive of metaphysical poetry. Shakespeare’s Ariel. John Donne.

Yet – to my mind & way of hearing – the excitement of Feldman’s music is in its simultaneous claim for & denial of sonic ‘purity’. As Beckett shows (& Feldman obviously absorbs Beckett’s lessons/lessens) paring down creates richness. Feldman’s single notes become voluptuous to the ear greedy for more. The attack, the duration, the fade. However, Cage also is instructive in the movement towards nothing – especially his ideas of continuity & no continuity, composition & acceptance - & implicitly denies minimalist preciosity.

Do ‘ideal’ conditions for Feldman’s music exist? Was he joking when he suggested a dead audience? As Cage frequently reminded us, you cannot attain silence. In the concert hall: the bronchitic in the third row, the air conditioning system, the hum of city traffic. In the domestic environment: your kids shouting downstairs, the CD player’s whirr. Even the iPod – does anyone load up Feldman CDs to go jogging? – is prone to distortion through mp3 compression, the rubbing & rustling of ear buds…

To say it again: you cannot speak of silence. No note is ‘pure’. I am reminded of Benedick in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’:

Now, divine air! now is his soul ravished! Is it not strange that sheep’s guts should hale souls out of men's bodies? (II. iii)

For me, Feldman’s music is predicated upon Cage’s “acceptance”. Continuity and no continuity. This applies ‘within’ the composition – although the spatial metaphor is rendered questionable by definition – as well as the context in which the composition is written, performed, heard. Background is foreground. Beginning, middle & end co-exist. Ventilated music such as Feldman’s cannot but embrace all sound. In this it is similar to a Calder mobile. Exquisitely balanced on its own terms yet also ‘accepting ‘ of the particular givens of ceiling to door jamb alignment, the faint breeze from the window, the startling snow-capped mountains (eg Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny).

Zappa spoke of his Project/Object whereby everything becomes part of the Work in Progress. A lyric, a chord, the cover art, a remark in an interview are all material for the Composition. A fabulous and liberating aesthetic of Life is Art (check out Out to Lunch, Poodle Play, and the Militant Esthetic site www.militantesthetix.co.uk) .

Feldman achieves it by different means. Precisely by paring music down to such minimal elements – seemingly purifying music of the contingency & noise of the everyday - Life rushes in through the holes. More than a glib play on words: the hole is the whole. What is ‘empty’? The oxymoronic ‘full emptiness’ makes sense.

For all their high art, minimalist chic packaging, Feldman’s CDs are not-things. What do we ‘buy’ when we purchase Early Piano Works? “It’s just a load of notes” is both a lazy opinion and penetrating analysis. (What, after all, is a de Kooning but “paint”?). We buy a duration – 78 minutes let us say – and a record of an interpretation. However, even the seemingly permanent status of the recording will - in its very playing and unfolding in time – be invaded by unforeseen circumstances, unheard of possibilities. I decide to listen to a Feldman piece, the CD starts, a fly enters the room – buzz, buzz, buzz – how irritating until you accept (that word again) the conditions of Feldman’s work.

“Let no one imagine that in owning a recording he has the music. The very practice of music, and Feldman’s eminently, is a celebration that we own nothing.” (Cage ‘Lecture on Something’).

Or, as Cage puts it later on in the same text:

“Let us say in life:/No earthquakes/are permissible”.

I listen to Feldman & hear what is there (& simultaneously not there) all the time. The whole in the holes. His divine holiness…

Feldman’s music intrigues me. It comes at the right time given my current reading & preoccupations. (Although during the MOMA Guston exhibition in Oxford circa 1987-8 wouldn’t have been a bad time, would it?). Still, we orbit.

How do you focus your ear? That seems to be a major issue with Feldman’s music. Cage, of course, wished his readers ‘Happy New Ears’. And it is not once every 365 days but here, now, this very second.

Which leads to a consideration of time. Feldman cites Varese & the “time sound needs in order to speak”. What is sound? What is a note in fact?

Feldman’s music demands a re-thinking of the material nature of sound. The note is struck – a physical action involving musician plus instrument (eg. piano = hammer plus strings) – which sets the air molecules “wiggling” (Zappa). The note is – as such – an after-image, a shadow. Feldman’s compositions are thus “thin air”. An “airy nothingness” suggestive of metaphysical poetry. Shakespeare’s Ariel. John Donne.

Yet – to my mind & way of hearing – the excitement of Feldman’s music is in its simultaneous claim for & denial of sonic ‘purity’. As Beckett shows (& Feldman obviously absorbs Beckett’s lessons/lessens) paring down creates richness. Feldman’s single notes become voluptuous to the ear greedy for more. The attack, the duration, the fade. However, Cage also is instructive in the movement towards nothing – especially his ideas of continuity & no continuity, composition & acceptance - & implicitly denies minimalist preciosity.

Do ‘ideal’ conditions for Feldman’s music exist? Was he joking when he suggested a dead audience? As Cage frequently reminded us, you cannot attain silence. In the concert hall: the bronchitic in the third row, the air conditioning system, the hum of city traffic. In the domestic environment: your kids shouting downstairs, the CD player’s whirr. Even the iPod – does anyone load up Feldman CDs to go jogging? – is prone to distortion through mp3 compression, the rubbing & rustling of ear buds…

To say it again: you cannot speak of silence. No note is ‘pure’. I am reminded of Benedick in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’:

Now, divine air! now is his soul ravished! Is it not strange that sheep’s guts should hale souls out of men's bodies? (II. iii)

For me, Feldman’s music is predicated upon Cage’s “acceptance”. Continuity and no continuity. This applies ‘within’ the composition – although the spatial metaphor is rendered questionable by definition – as well as the context in which the composition is written, performed, heard. Background is foreground. Beginning, middle & end co-exist. Ventilated music such as Feldman’s cannot but embrace all sound. In this it is similar to a Calder mobile. Exquisitely balanced on its own terms yet also ‘accepting ‘ of the particular givens of ceiling to door jamb alignment, the faint breeze from the window, the startling snow-capped mountains (eg Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny).

Zappa spoke of his Project/Object whereby everything becomes part of the Work in Progress. A lyric, a chord, the cover art, a remark in an interview are all material for the Composition. A fabulous and liberating aesthetic of Life is Art (check out Out to Lunch, Poodle Play, and the Militant Esthetic site www.militantesthetix.co.uk) .

Feldman achieves it by different means. Precisely by paring music down to such minimal elements – seemingly purifying music of the contingency & noise of the everyday - Life rushes in through the holes. More than a glib play on words: the hole is the whole. What is ‘empty’? The oxymoronic ‘full emptiness’ makes sense.

For all their high art, minimalist chic packaging, Feldman’s CDs are not-things. What do we ‘buy’ when we purchase Early Piano Works? “It’s just a load of notes” is both a lazy opinion and penetrating analysis. (What, after all, is a de Kooning but “paint”?). We buy a duration – 78 minutes let us say – and a record of an interpretation. However, even the seemingly permanent status of the recording will - in its very playing and unfolding in time – be invaded by unforeseen circumstances, unheard of possibilities. I decide to listen to a Feldman piece, the CD starts, a fly enters the room – buzz, buzz, buzz – how irritating until you accept (that word again) the conditions of Feldman’s work.

“Let no one imagine that in owning a recording he has the music. The very practice of music, and Feldman’s eminently, is a celebration that we own nothing.” (Cage ‘Lecture on Something’).

Or, as Cage puts it later on in the same text:

“Let us say in life:/No earthquakes/are permissible”.

I listen to Feldman & hear what is there (& simultaneously not there) all the time. The whole in the holes. His divine holiness…

Saturday, May 20, 2006

Friday, May 19, 2006

Out building

There is the story of the man whose job in the factory was to turn a tap on and off at designated times each day. He did his job faithfully, didn’t call in sick, took his breaks according to the regulations. On his retirement, he was presented with the usual recognition for his labour and loyalty to the company. A short time afterwards it was discovered that the pipe had silted up – and this had been the case for many years.

An allegory, perhaps, for the Blogger? Composing daily entries in the fond belief they have a purpose and/or audience, only to discover that they are without reader, flat on the page.

So why Blog? One reason is to discover this first hand. I don’t know. I will Blog to find out. I already keep a notebook (and why do this … we can play the game ad infinitum) which does the job pretty well.

A Calvinist haunting? Justifying one’s days? Proving one’s deserving since - if you are one of the ‘chosen’ - you would be doing this anyway?

Emily Dickinson’s fascination with bees, the “humble” worker. The bee who works away regardless of fame or fortune distilling his labours into honey. A poetic conceit (free of conceitedness) and a religious expression of Faith and Belief. And Dickinson’s vast output of over 1,700 poems hardly any of which were published during her lifetime. Writing for a rainy day? A devout projection into the future? A bid for Eternity?

Might the Blogger’s time be better spent? Do something concrete!

Notebook keeping is – as such – private. You write without thought that anyone will read it. It is a way of drawing materials together, a gathering, how materials rub against each other, one thing leads to another. Or, simply, an aid to memory. Or, a workshop – a place to dissect and experiment.

Blogging is going ‘public’ – at least it presupposes an ‘Other’ who is or might be reading. Yet for the Blogger it is also an experience of ‘Othering’. The “I” tapping the keys is distinct from the “I” being composed in – where? – this ‘atopia’of Server, Web, digital media. In a sense you ‘hear’ yourself coming back at yourself. An echo of sorts. Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” as the basic formula of writing. These are well-established ideas but is quite another thing to feel them as you hit the publish button. These words - 'here' - are now ‘out there’.

Maybe this is what is being constructed: a kind of ‘out building’. Not part of the main house but attached in some ways. It has windows through which the passerby can peer. Something’s going on in there but no one is quite sure what.

An allegory, perhaps, for the Blogger? Composing daily entries in the fond belief they have a purpose and/or audience, only to discover that they are without reader, flat on the page.

So why Blog? One reason is to discover this first hand. I don’t know. I will Blog to find out. I already keep a notebook (and why do this … we can play the game ad infinitum) which does the job pretty well.

A Calvinist haunting? Justifying one’s days? Proving one’s deserving since - if you are one of the ‘chosen’ - you would be doing this anyway?

Emily Dickinson’s fascination with bees, the “humble” worker. The bee who works away regardless of fame or fortune distilling his labours into honey. A poetic conceit (free of conceitedness) and a religious expression of Faith and Belief. And Dickinson’s vast output of over 1,700 poems hardly any of which were published during her lifetime. Writing for a rainy day? A devout projection into the future? A bid for Eternity?

Might the Blogger’s time be better spent? Do something concrete!

Notebook keeping is – as such – private. You write without thought that anyone will read it. It is a way of drawing materials together, a gathering, how materials rub against each other, one thing leads to another. Or, simply, an aid to memory. Or, a workshop – a place to dissect and experiment.

Blogging is going ‘public’ – at least it presupposes an ‘Other’ who is or might be reading. Yet for the Blogger it is also an experience of ‘Othering’. The “I” tapping the keys is distinct from the “I” being composed in – where? – this ‘atopia’of Server, Web, digital media. In a sense you ‘hear’ yourself coming back at yourself. An echo of sorts. Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” as the basic formula of writing. These are well-established ideas but is quite another thing to feel them as you hit the publish button. These words - 'here' - are now ‘out there’.

Maybe this is what is being constructed: a kind of ‘out building’. Not part of the main house but attached in some ways. It has windows through which the passerby can peer. Something’s going on in there but no one is quite sure what.

little Workmanships

Stitching, sewing, weaving, the sewn fascicles... Emily Dickinson's textual-textiles. But what about webs? The web as spiral (labyrinth, trap, circling in, spinning out, coiled energy). The web as 'acoustic' structure - the spider creates a tension in the web to then be able to 'hear' the arrival of the victim. Thus a web is - as such - a construction upon lines of sound. The implications for a poetics are clear.

Thursday, May 18, 2006

The secret love child of Gertrude Stein?

Ear Sculpture

Early Piano Works - Morton Feldman

Hex Enduction Hour & BBC Peel Sessions - The Fall

Floating World - Soft Machine

Hex Enduction Hour & BBC Peel Sessions - The Fall

Floating World - Soft Machine

All Change At Reading

As In Every Deafness - Graham Foust

Give My Regards to Eighth Street - Morton Feldman

Telepathy - Devin Johnston

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

The Sonnets - Ted Berrigan

Silence - John Cage

Give My Regards to Eighth Street - Morton Feldman

Telepathy - Devin Johnston

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

The Sonnets - Ted Berrigan

Silence - John Cage

Construction I

"I have seen vast multitudes of little shining webs and glistening strings, brightly reflecting the sunbeams, and some of them of a great length, and at such a height that one would think that they were tacked to the vault of the heavens ..."

(Jonathan Edwards, 1723)

"If,/going/to some place, we/had/first to settle how/to put/the front foot down, we should/never get there./If the painter/had to plan out every/brush-mark before he/made/his/first/he would not paint at all./Follow/your principles/and keep/straight on;/you will come to the/right place,/that is the way."

(John Cage, 1959)

(Jonathan Edwards, 1723)

"If,/going/to some place, we/had/first to settle how/to put/the front foot down, we should/never get there./If the painter/had to plan out every/brush-mark before he/made/his/first/he would not paint at all./Follow/your principles/and keep/straight on;/you will come to the/right place,/that is the way."

(John Cage, 1959)

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

April Fool?

-

"Not long after his death in 1978, Zukofsky was taken up by a group of young writers who referred to themselves as the L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E ...